We are now well into autumn, the season of mists and mellow fruitfulness (according to John Keats) and what’s more, we are well into October, the month of shrieks and gore, according to Prime and Hulu and Netflix and the other streamers, all of which are offering up full slates of horror movies in preparation for the bacchanalia of fright, candy, and cosplay on the 31st. (The Roku collection is called “Stream & Scream”, naturally.)

The horror movie — thanks in large part to those aforementioned streaming services — has apparently never been in better health, at least if we’re measuring nothing more than quantity. Quality is of course an up-and-down, hit-and-miss attribute in any era, but the never-ceasing torrent of “content” (hate that word) simultaneously issuing from so many different “platforms” (another ugly expression) may make it harder than ever to discern the diamonds among the detritus.

But that’s what Black Gate is for, right? We’re here to lift the burden from your tired shoulders and make life easy for you! Therefore, may I suggest for your Halloween season viewing… drumroll, please… a creaky, black-and-white warhorse that’s damn near a hundred years old?

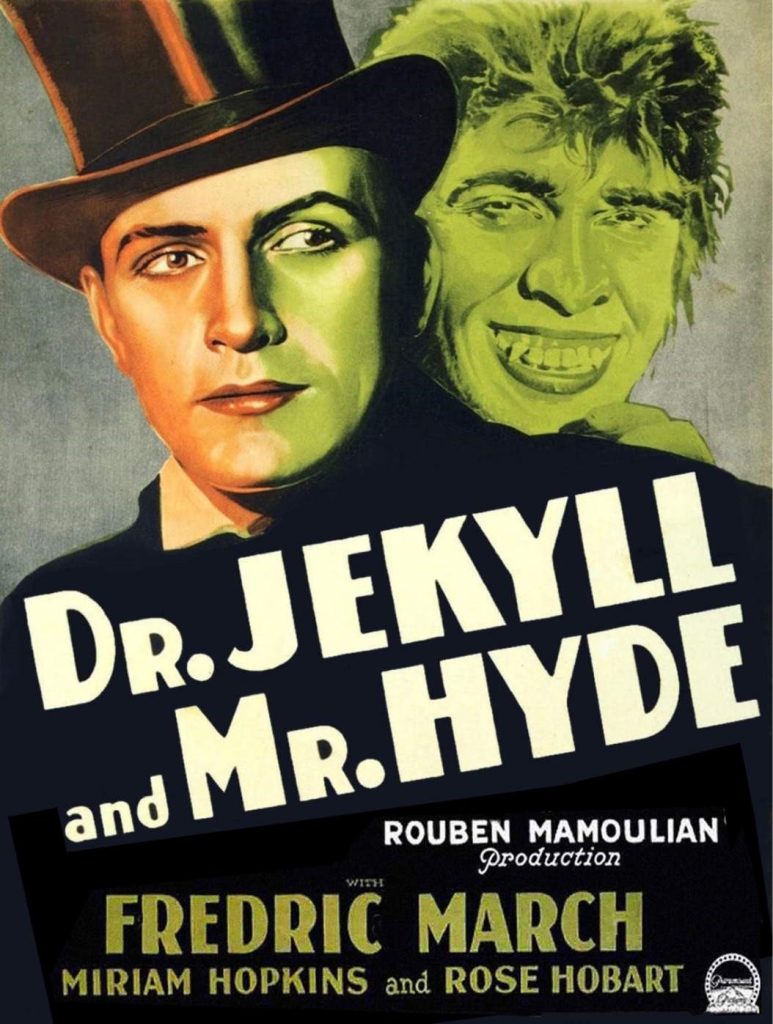

No, I’m not kidding. I am here to seriously assert that the best horror movie you can watch right now is not some newly-minted fright-fest flung fresh from the gaping maw of the Entertainment-Industrial Complex, but the 1931 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Only God (or IMDb) knows how many film versions of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novella there are; whatever the number, it must surely be one of the most filmed and refilmed stories ever written, and that’s without counting all the times it’s been travestied on television sitcoms. (I promise not to mention the time it was done on Gilligan’s Island. Some things are just too horrible to contemplate, even for people as blood-soaked and cynical as you and me.)

Once Hollywood gets its hands on something, there’s no telling what will happen to it. Period and locale can change, genders can be bent (as in 1998’s Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde), and the terrifying can become comedic (as it did in 1963’s The Nutty Professor, Jerry Lewis’s brilliant riff on the split personality theme). All stories famous enough to be frequently adapted are subject to such treatment, but if the original tale is strong enough, it can survive almost any amount of manhandling.

This is certainly true of so serviceable and resonant a story as Stevenson’s — his book has gone through some radical (and sometimes ill-advised) surgeries since it was first filmed in 1908, but it’s still standing after more than a century of versions and variations. Many of those efforts are worthwhile viewing, but even so, the 1931 film produced by Paramount Pictures has a strong case for still being the best “straight” adaptation of the story. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starring Fredric March as the unfortunate physician and his brutish alter-ego, it’s a movie that never fails to thrill, chill, and even shock me every time I see it.

Born in Russia to Armenian parents, Rouben Mamoulian began his career as a stage director, showing a special aptitude for musicals (he directed the first productions of Rogers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma and Carousel and George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess). A flair for theatrically bold staging combined with innovative camera movement became Mamoulian’s trademark when he moved from Broadway to Hollywood, and these flamboyant skills were ideal for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a movie (his third) in which he utilizes split screen (no need to say why that’s appropriate for this story) and a great many of point of view shots, literally placing us in Jekyll’s head.

Born in Russia to Armenian parents, Rouben Mamoulian began his career as a stage director, showing a special aptitude for musicals (he directed the first productions of Rogers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma and Carousel and George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess). A flair for theatrically bold staging combined with innovative camera movement became Mamoulian’s trademark when he moved from Broadway to Hollywood, and these flamboyant skills were ideal for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a movie (his third) in which he utilizes split screen (no need to say why that’s appropriate for this story) and a great many of point of view shots, literally placing us in Jekyll’s head.

Most importantly, Mamoulian isn’t shy about putting the film’s themes right there on the screen where they can be seen. In a story laden with symbolic and allegorical overtones, the director fills the frame with mirrors (our dual nature), skulls and skeletons (the inevitability of death, of course, but perhaps even more the grim realities that often lie hidden beneath pleasing surfaces) roaring flames (dangerous knowledge) and the roiling, boiling cauldrons, alembics, and retorts of Jekyll’s laboratory (the repressed thoughts and desires that can build pressure until they explode disastrously and overwhelm our more civilized impulses).

Such nakedly obvious devices would be risible in a realistic drama, but they are perfect in Stevenson’s gothic-tinged fable (and remember that sound had arrived a mere four years before with 1927’s The Jazz Singer). At the end of the film, when Mamoulian holds his camera on the police detective who has just shot Mr. Hyde, and then has the actor suddenly lean to the side to reveal the skeleton hanging behind him, the dead face instantly appearing next to (seemingly emerging from) the living one, you may smile at a trick so transparent that no one would dare to use it today, but even more at how perfectly, poetically apt the image is.

The last thing we see in the film, in fact, is a picture that visually sums up the entire story — in the background, the dark shambles of the late Dr. Henry Jekyll’s workshop, and in the foreground, a cauldron in which some thick, viscous-looking liquid is boiling, finally explosively overtopping the vessel’s rim in a scalding torrent. Having watched the movie to the end, we know what that dangerous effusion is, because Mamoulian has made it perfectly clear — it’s our human sexual nature, something best handled very carefully, neither completely bottled up nor let loose with no restraints at all.

It’s startling to see a film of this vintage deal so frankly with such a theme, but Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is a “pre-code” movie, and the studios were able to get away with far more than they could after 1934, when the production code began to be strictly enforced. The flashes of nudity, Jekyll’s undisguised sexual frustration caused by the delay of his marriage with Muriel Carew (Rose Hobart), and the overtly sadomasochistic relationship between Hyde and the low-class, sexually available Ivy Pearson (Miriam Hopkins) have all vanished or been severely muted in the next major version, the 1941 MGM film with Spencer Tracy and Ingrid Bergman, directed by Gone with the Wind’s Victor Fleming.

That film avoids the issue rather than confronting it, and has to make do with clunkingly “Freudian” dream sequences (a sweaty Tracy abusing horses instead of Bergman). You begin to wonder, “Just what is this guy’s problem, anyway?” Mamoulian had the freedom to take a more direct approach, and it’s far more effective.

The real reason to still see this old movie, though, isn’t its striking production design, sharp direction, or pre-code frankness; it’s Fredric March’s performance as Mr. Hyde. His Henry Jekyll is a perfectly credible high-spirited good guy… and who cares about characters like that? What we want are great villains; show us an appalling, terrifying monster and we will love it forever, and March’s Mr. Hyde is one of the greatest in the history of movies. The performance is so good, in fact, that it won March the Academy Award for Best Actor, still the only Best Actor ever awarded for a performance in an outright horror movie. (I know — Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs and Joaquin Phoenix in Joker, but I consider those movies as at best horror-adjacent rather than true horror. You wanna fight about it? Let me drink this first…)

March’s Hyde is still sometimes dismissed as a “make-up” performance, and there’s no doubt about it — the Hyde make-up (by the legendary Wally Westmore) is still frighteningly effective, even after so many decades. But the make-up only facilitates March’s riveting performance — it isn’t the performance itself, which remains astonishingly brave and uncompromising.

The first time Jekyll quaffs his concoction and becomes Hyde, the repressed alter-ego has a lot of our sympathy. At first the distinctly simian Hyde doesn’t look so bad — like a cheerful chimpanzee — and his elation at being released from his bondage is palpable. After nervously hiding behind a screen and looking around to see if anyone is there to chastise him, he stretches his body luxuriously, as if he’s been squeezed and cramped his whole life. (The sheer physicality of the performance is one of the best things about it; twitching, creeping, crouching, shambling, leaping, running, snarling, lashing out at any annoyance, the restless Hyde is always in motion.)

The first time Jekyll quaffs his concoction and becomes Hyde, the repressed alter-ego has a lot of our sympathy. At first the distinctly simian Hyde doesn’t look so bad — like a cheerful chimpanzee — and his elation at being released from his bondage is palpable. After nervously hiding behind a screen and looking around to see if anyone is there to chastise him, he stretches his body luxuriously, as if he’s been squeezed and cramped his whole life. (The sheer physicality of the performance is one of the best things about it; twitching, creeping, crouching, shambling, leaping, running, snarling, lashing out at any annoyance, the restless Hyde is always in motion.)

His toothy grin as he looks at himself in the mirror is positively appealing, and when he exults, “Free! Free at last!” we’re largely on his side. The first time he goes outside and stands with his head uplifted, glorying in the feeling of the rain running off his face, we like him rather more than we’ve ever liked the pompously pontificating Jekyll.

In the beginning, Hyde seems more mischievous than evil, as when he sticks his cane up an old woman’s skirt and runs off giggling; he’s eager for experience, and we can easily understand why, but when he arrives at the music hall where Ivy Pearson works, his true nature quickly reveals itself.

Jekyll had earlier come to Ivy’s aid in an altercation with some ruffians, and she had been strongly attracted to the gallant gentleman doctor. (The naked and well-endowed Hopkins sitting up in her bed, barely covering herself with a sheet and blanket, sensuously swinging her bare leg back and forth as she whispers, “Come back soon, won’t you? Come back… come baaaack” to the departing and cheerfully dismissive Jekyll, is one of those scenes that can make you say, “When was this move made?!”)

Jekyll may have forgotten Ivy, but Hyde certainly hasn’t, and only a few minutes pass before he has lured her to his table with a bottle of champagne (there’s a song that she sings in the music hall — “Champagne Ivy is my name…”), and before the encounter is over, he has flattered and then bribed and then bullied and finally terrorized her into becoming his mistress.

Miriam Hopkins as Champagne Ivy

Hyde sets her up in a room which, for all of its luxury and comfort, is nothing more than a cage where he can come to torture her, and torture her he does, leaving her body covered with welts and bruises, all while sneeringly declaring his “love” for her. The sexual sadism is unveiled and deeply disturbing, as Hyde torments the helpless Ivy in every conceivable way. (At their first meeting in the music hall, after he grabs her roughly, he gives her a preview of her future when he says, “I hurt you because I love you!”)

The nature of the unfortunate Ivy’s relationship to her keeper comes across with crystal clarity in the following exchange:

Sit down so that I can look at you, my sweetling. Say it aloud.

What do you mean?

Don’t you think I can read your thoughts, you trull? You hate me, don’t you? I’m not good enough for you! I’m not a nice, kind gentleman like that — Nice, kind gentlemen who are so good to look at and so — Cowards! Weaklings! Tell me you hate me. Please, my lamb, please my dear, sweet, pretty little bird, tell me that you hate me!

I don’t know what you mean.

Don’t you, my lamb? Then you don’t hate me, eh?

No sir.

If you don’t hate me, you must love me. Isn’t that so, my little one? Isn’t it!?

Yes sir.

Ahh, how you must love me. I want to hear you say it. Say it. Come on — say it! Say it! Say it!!

Yes sir!!

After working Ivy up to near-hysteria, Hyde then makes the weeping girl sing her song for him while he gloats over her terror; he seizes her and runs his coarse hands all over her quailing body and when she swoons, clasps her to him in a grisly kiss. And all the while he makes it clear that there is no escape for her: “Remember you belong to me, do you hear? You belong to me! And if you do one thing that I don’t approve of while I’m gone, the least little thing, mind you — I’ll show you what horror means!”

These stomach-wrenching scenes are hard to watch. March holds nothing back (and neither does Hopkins; she gives a powerfully moving performance despite having one of the worst English accents ever immortalized on celluloid); where a less courageous actor would hedge his bets, worrying about what playing such a vile and vicious character might do to his public standing, March’s commitment is total; at every opportunity he goes deeper into Hyde’s violence and sadism. (For a real dose of schizophrenia, follow up a viewing of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by watching Ernst Lubitsch’s effervescent sex comedy, Design for Living, made only two years later, where March and Hopkins team again, this time with delightful results. You won’t know whether you’re coming or going.)

The whole thing comes to a head when Ivy goes to Jekyll for help and the remorseful doctor promises her that he will see to it that Hyde never returns. Jekyll intends to keep his promise; the date of his wedding has been moved up and he’s going on the wagon, so to speak; he is determined to never use his formula again. But shortly after his meeting with Ivy, for the first time the transformation happens spontaneously. (It’s prompted by a chance act of violence; while walking in the park, Jekyll happens to see a cat kill a songbird, and the change begins immediately afterward.)

Ivy believes Jekyll’s promise; while the doctor is undergoing his change in the park, she sits in her room glorying in her deliverance and happily wishing Hyde in hell. We can see the door behind her as she curses Hyde and makes optimistic plans for her future; we can see it, knowing that in a moment it will slowly open and the doomed girl’s death will walk through it. When the door does open, Ivy’s fear and despair are total — as are ours.

Ivy cannot believe that her benefactor has betrayed her, and to show her she’s wrong, Hyde tauntingly repeats the very words she used when pleading with Dr. Jekyll (the “canting hypocrite” that Hyde hates more than any other man): “I’ll slave for you — I’ll love you — you’re an angel, sir!” The stunned girl slumps against the wall and Hyde mercilessly pronounces her fate: “You wanted him to love you, didn’t you? Well, I’ll give you a lover now — his name is Death!” The moment — the whole film, really — is so heightened as to be virtually operatic. (It may take you many viewings to realize that there is no underscoring anywhere in the movie; once the opening credits are over, music is only heard the few times Jekyll or Muriel play the organ or piano. Anything else would be redundant.)

To make the girl’s last moments even more agonizing, Hyde administers a final twist of the knife, the cruelest of all: “I’m going to let you into a secret — a secret so great that those who share it with me cannot live — I am Jekyll!” He then throws Champagne Ivy to the floor and strangles her. The camera mercifully stays focused above floor level, and all we see is a beautiful sculpture of two embracing angels… while we hear Ivy’s death rattle as her murderer gently croons, “Isn’t Hyde a lover after your own heart?” It’s amazing that such a shocking, unrelenting slice of darkness ever made it into a popular entertainment.

By this time Hyde has almost played out his string; he has just one more crime to commit. Pursued by the police, he visits Jekyll’s friend Dr. Lanyon (Holmes Herbert), who has been entrusted with the elements of the transformation formula (without knowing what they are for). Hyde mixes the ingredients together and uses the drink to change back into Jekyll, who then tells his story to Lanyon; with his awareness of his crimes, he is now a broken man.

Jekyll pays a visit to Muriel and in a frenzy of remorse breaks their engagement as an act of penance. He rushes out of the house as Muriel collapses with grief, but rashly continues to lurk outside, watching her through the window… and the sight of her agony sparks one last spontaneous change. With each successive appearance Westmore has made the make-up more and more extreme; now, in his final appearance, every trace of Hyde’s initial impish charm has vanished; he scarcely looks human at all. He has become nothing but a grotesque, obscene beast.

Jekyll pays a visit to Muriel and in a frenzy of remorse breaks their engagement as an act of penance. He rushes out of the house as Muriel collapses with grief, but rashly continues to lurk outside, watching her through the window… and the sight of her agony sparks one last spontaneous change. With each successive appearance Westmore has made the make-up more and more extreme; now, in his final appearance, every trace of Hyde’s initial impish charm has vanished; he scarcely looks human at all. He has become nothing but a grotesque, obscene beast.

Now all of the illusory appeal of evil’s false freedom is gone; all that remains is horror and degradation and death. (Even articulate speech has disappeared — from now until the end of the film, the only sounds that issue from Hyde are bestial growls and snarls.) Hyde is on the verge of attacking Muriel when her father (the man who had obstinately delayed Jekyll’s marriage) comes into the room, and with savage brutality, Hyde leaps on the old man and beats him to death with his cane. It only remains for the monster to flee back to Jekyll’s laboratory, where he will be shot to death by the police. It would indeed seem that there are some fires best left unkindled, some doors that should never be opened.

Fredric March’s performance in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is beyond praise. Such is his skill that it’s easy to forget that one actor is playing both characters. Of course the superb make-up changes the face, but as Hyde the greatest change March conveys is an inner one; he speaks differently, stands differently, moves differently, and there’s a different look in his eyes — you can see him thinking and feeling and reacting differently, and yet… when Hyde mixes his formula in front of Dr. Lanyon, before he drinks it, he boasts of his genius in creating it in the face of the doubts and opposition of petty, small-minded men, and in his voice you can momentarily hear both Jekyll and Hyde, speaking together, true brothers under the skin, alike in their pride and recklessness.

Ninety-three years ago, with the help of Rouben Mamoulian and Wally Westmore, (and Miriam Hopkins), in a performance for the ages, Fredric March was brave enough to go all the way in sounding untold depths of terror and violence and depravity, emerging on the other side to touch a strain of tragedy that you don’t find in many horror movies — of any vintage.

So, how brave are you? Surely if you’re brave enough to Stream & Scream, brave enough to face Chucky and Jason and Paranormal Activity, you ought to have the courage to watch a black and white relic like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. After all, everyone connected with this museum piece has been dead for fifty years, so what is there to be afraid of?

Nothing. Nothing… except maybe that other self that you sometimes catch a glimpse of in the mirror. I don’t know about you, but as far as I’m concerned, Chucky’s got nothing on that guy.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Margaret Hamilton: Wicked Forever